In 2021, systems integrator CRG Automation successfully completed an unprecedented project to automate the process of disarming, disassembling and destroying 70,000 aging rockets filled with deadly nerve agents.

The project was implemented at the Blue Grass Army Depot in Richmond, KY. To complete the project, we worked closely with several organizations and companies:

- The U.S. government’s Program Executive Office—Assembled Chemical Weapons Alternatives (PEO ACWA).

- Bechtel Parsons Blue Grass, a joint-venture between construction firm Bechtel Corp. and Parsons Corp., an engineering firm specializing in defense, security and infrastructure projects.

- Amentum Services Inc., a technical and engineering services firm specializing in defense work.

- DynaSafe, a manufacturer of explosive containment chambers and other equipment for destroying munitions.

- Crown Packaging Corp., a supplier of conveyors and other equipment.

CRG Automation is an engineering firm best known for building packaging lines for the likes of Coca-Cola, Kellogg’s and Kraft. We have been designing and building packaging and processing equipment for the food, beverage and consumer products industries for more than 23 years. Over time, repeat customers approached us with more and more complex problems.

Aging mortar rounds filled with mustard agent must be handled carefully. Photo courtesy U.S. Army Pueblo Chemical Agent-Destruction Pilot Plant

Today, CRG continues to offer cartoners, case packers and other packaging equipment, but it has expanded its services to include custom automated assembly and manufacturing lines. The firm’s Louisville headquarters includes a modern machine shop and ample space to build and test large automated systems.

Our project in Kentucky was so successful that the Army came back to us with another task: Create an automated system to disassemble and destroy thousands of mortar rounds filled with highly toxic mustard agent. The rounds were stored at the Pueblo Chemical Agent-Destruction Pilot Plant (PCAPP) in Pueblo, CO, and would have to be destroyed by the end of 2023.

A robotic system originally planned for the complex, 4.2-inch mortar rounds presented increased risks to workers and maintainability challenges compared with existing systems built to disarm 105- and 155-millimeter projectiles.

This was unlike anything we had ever dealt with before. Having solved so many challenges in Kentucky, though, we knew this would be another project that would excite our engineers, who thrive on the kinds of problems that frustrate other firms.

“This was [going to be] much, much harder,” says Ken Ankrom, project manager for Amentum, adding that the regulatory requirements would be “more far-reaching than anything we’ve dealt with.”

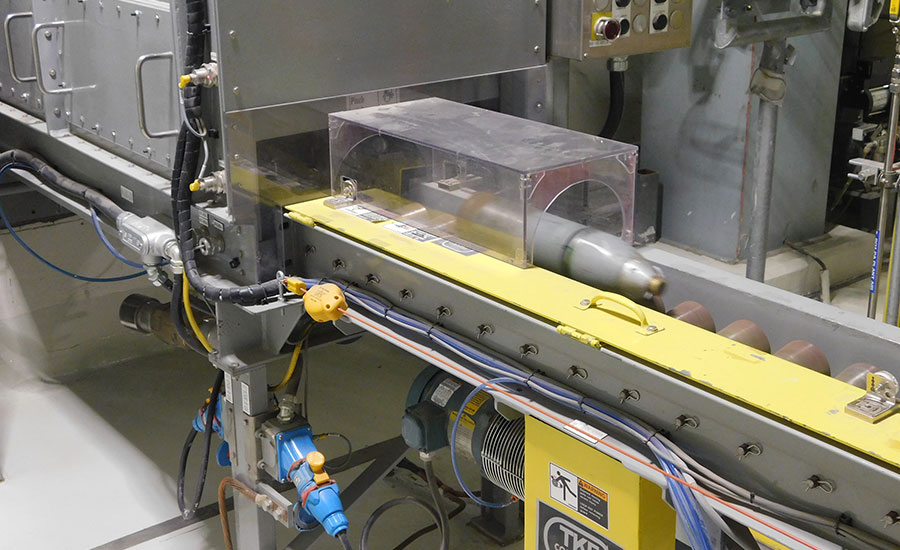

A 4.2-inch mortar round sits on a conveyor. The conveyor moves munitions into an explosion containment room, where a disassembly system removes the energetics and explosive parts. Photo courtesy U.S. Army Pueblo Chemical Agent-Destruction Pilot Plant

With the challenge in front of us, the Kentucky team reunited and began work in September 2021. We would have to adhere to a strict set of guidelines:

- The system would have to function in a caustic environment.

- Each mortar round included a welded, immovable baffle assembly that ran through the center of the agent cavity. Mustard agent often caked onto the baffle assembly over time. Our system would need to be able to completely rinse out the agent, thick or thin, in the interior of the shell, as well as on the baffle assembly.

- The interior would only be accessible through a 0.75-inch opening created by the removal of the mortar’s burster well assembly casing.

- The system would need to fit exactly on the existing cavity access machine (CAM) pads, using existing utilities. Nothing could be added.

- The system would have to be strictly reviewed by state authorities, which could cause delays in the timeline.

For Kim Jackson, manager of the PCAPP, the vision was clear, but achieving it in such a compressed time frame might prove impossible. “We knew this had to be right, right out of the gate,” she says. “We had intense requirements from the regulators, and we knew we had to meet special requirements for design.”

Jackson thanked CRG for its approach to what became known as the Improved Cavity Access Machine (ICAM) project. CRG’s engineers examined both short-term and long-term needs at the outset. “What CRG did at the very beginning to set us up for success made all the difference,” she says.

A Crucial First Step

To hasten the project, the team quickly developed and assembled an X-ray device to examine which mortar shells would be most challenging, given the mustard agent’s varying degrees of solidification. With the scope of the problem identified, the team set about developing ways to remove the agent safely and efficiently.

The team quickly implemented a way to pull the burster well assembly from the mortar, and then began the process of designing a system that could both vacuum out the liquefied mustard agent, while also washing any solidified agent off the baffle. The system would have to ensure that none of agent leaked, creating a hazard in the processing area.

Complicating the issue was that some of the mortars had become pressurized over time. Removing the burster well would sometimes lead to a bit of frothiness, similar to opening a bottle of champagne.

Our team set about designing a system that would first introduce a tube into the mortar to vacuum up liquefied mustard agent, including anything that might immediately swell up from the removal of the burster well.

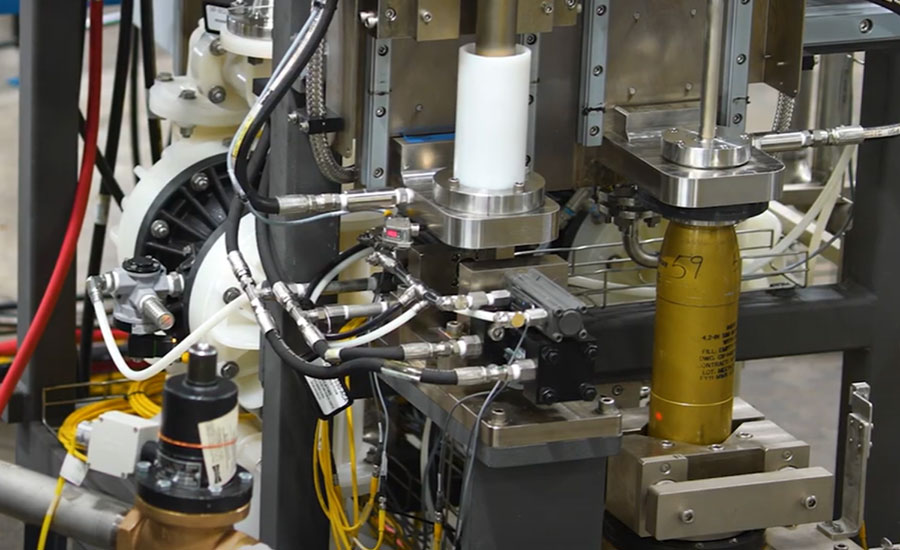

CRG engineers designed a system that introduces a tube into a mortar round to vacuum up liquefied mustard agent, including anything that might immediately swell up from the removal of the burster well. Photo courtesy U.S. Army Pueblo Chemical Agent-Destruction Pilot Plant

As the vacuum reached a midway point in the mortar, a wash wand with 10 nozzles would begin a high-pressure wash using three gallons of water per minute. While this took place, the ICAM rotated the mortar 180 degrees, back and forth, to ensure the mustard agent was fully washed out from the interior and baffle surfaces.

The system was designed virtually using computational fluid dynamics, quickly proving that the concept would work. This was essential given the finished technology involved five subsystems and more than 2,000 parts.

Jackson complimented CRG’s innovative approach to the problem, as requirements initially called for using higher pressures, which could have further complicated the destruction process. Because of CRG’s unique approach, “We washed the mortars out to bare metal clean following additional optimization at PCAPP,” Jackson says.

CRG proactively made sure to involve and train Jackson’s workforce on the innovative approach. “When you’re doing something that people aren’t familiar with, you’ve got to close the knowledge gap and make sure they understand the automation and the possibilities to improve, and CRG did that,” Jackson says.

The team also developed a containment manifold to fit around the top of each mortar to capture any agent coming out as the vacuum and wash wand tackled the inside. “That was one of our biggest challenges,” Ankrom says. “It took the entire team siting down and looking at the machine. We not only figured out how to contain the agent and the wash water, but also how to contain them under different mustard conditions.”

This image shows an off-gas treatment system (OTS) for one of three static detonation chambers. Gases generated from the detonation or deflagration of mortar rounds and other projectiles are treated by an OTS, which includes a thermal oxidizer to convert carbon monoxide and hydrogen to chloride salts and sulfates. Photo courtesy U.S. Army Pueblo Chemical Agent-Destruction Pilot Plant

Building the System

With the process developed, CRG set about fabricating the machinery. With such a tight timeline to meet international treaty deadlines, the company invited the Colorado plant employees to join its team in Louisville to participate firsthand in the construction and initial testing of the ICAM.

“For CRG to be willing to let us join them on their factory floor and put our hands on the equipment at that stage made a huge difference” Jackson says.

“It was not just the operations and maintenance staff, we had the control system people there, too,” adds Ankrom. “If they saw something that would help them, they said it right there. Everybody knew what we were doing, and why we were doing it.”

Ankrom thanked CRG for its dedication to bringing everyone together to observe, ask questions, understand, and test the system. “As always, it just went exceptionally well,” he says.

The process water tank in each static detonation chamber unit provides recycled water to help maintain temperature during operation. Photo courtesy U.S. Army Pueblo Chemical Agent-Destruction Pilot Plant

Installation Accommodations

With so many existing systems in Pueblo’s facility, it was essential for the team to develop the ICAM within the current setup. “Integrating this machine into the plant was a challenge,” says Pueblo plant support specialist Randy Johnson, noting that the installation of the ICAMs into the facility requires workers to wear hazardous suits.

“You can only go in for 90 minutes at a time. It’s very difficult to install anything with those kinds of restrictions. The whole time we’re designing this, we’re thinking about how people in suits with five layers of gloves have to work on this,” Johnson says. “Small screws and bolts aren’t really an option.”

Johnson praised the development team at CRG: “They’re a really good group of people—very responsive and very willing to listen and solve problems. You can’t say enough good things.”

Not only did the team design the system within the same footprint of the original CAM, the team was also able to reprogram the existing robots that Pueblo’s staff hoped to continue to use. “CRG bent over backwards so we could keep using what we had,” Johnson says.

CRG sent a series of engineers to the Colorado plant prior to installation to train the employees who had been unable to visit during the development. “They lived in our plant,” says Jackson, who had anticipated the installation process would take 60 days. Instead, because of the constant collaboration and the team’s approach, it took just 21.

That’s faster than the industry standard of 42 days for just a simple conversion of existing equipment. “We’re talking about brand new systems here,” Ankrom says.

At CRG, we believe in constant communication and collaboration. When you do that upfront, it always pays off in the end, as you can accomplish your mission more quickly, efficiently and safely. Everyone wins.

Ordnance technicians prepare 4.2-inch mortar rounds for destruction inside the static detonation chamber complex. Once workers load the munitions into boxes, a conveyor transports them to the detonation chamber, where they are destroyed. Photo courtesy U.S. Army Pueblo Chemical Agent-Destruction Pilot Plant

Building to the Best Performance

With the eight ICAM stations installed, the Colorado team began its work destroying the most complicated of the weapons.

Prior to reaching the ICAM, each mortar has its fuse and explosive burster charge removed in a separate operation. Once introduced into the demilitarization facility, the disarmed mortars are moved by robots to an ICAM station. There, a steel tube extractor device pulls out the burster well. The vacuum tube is inserted at the next station to remove the mustard agent. That is followed by an 80-second high-pressure wash within the mortar’s agent cavity, which completely rinses out the contents.

The plant’s agent collection system sends the collected mustard agent for further processing by a neutralization system. While that takes place, the station that removed the burster well punches four vent holes in its bottom. Then, the well is partially reinserted back into the mortar. The munition bodies are then processed through a metal part treatment unit at a temperature exceeding 1,000 F, which ensures the complete destruction of any remaining chemical agent.

As the ICAM devices performed their work in such a caustic environment, an issue arose with sensors developing corrosion. With just five weeks to go before anticipated completion, taking a number of machines offline for repairs or replacement could have derailed the entire project, but the team had planned ahead.

“The team responded again, and we rebuilt these ICAMs on the fly,” Jackson says. “I loved that our people had already been brainstorming ‘What if this fails in operation,’ ‘What if we have to replace a vacuum pump.’ They were already thinking of the vulnerabilities and how to fix them. We were ultra prepared.”

Ordnance technicians prepare 4.2-inch mortar rounds for destruction inside the static detonation chamber complex. Once workers load the munitions into boxes, a conveyor transports them to the detonation chamber, where they are destroyed. Photo courtesy U.S. Army Pueblo Chemical Agent-Destruction Pilot Plant

The Colorado employees exceeded all expectations in making repairs. The process takes just one entry into the destruction area by one person instead of the expected eight. “It goes back to the spirit of collaboration that happened on CRG’s shop floor,” Jackson says. “It’s what drove that attitude and mentality and that ownership.”

The repairs succeeded and the plant finished destruction operations ahead of schedule. Without the wash-out system, Jackson predicts the plant would have finished several months after the treaty deadline. Instead, though, the collaborative effort saw the plant achieve its most efficient processing during the final weeks with the most complex of the mortar rounds.

“Everyone had said your best performance will be during the easier agent rounds,” Jackson says. “When in reality, our best performance was with our pressurized solid-heeled rounds at the bitter end.”

Reflecting on the project’s success, Ankrom described it as “the fastest single demilitarization project I’ve ever worked on and delivered.”

He thanked CRG for “shining” throughout and noted how he had once told superiors that “if we’re going to get this done, we’re going to have to turn to industry.”

“I have not once ever regretted those words in working with CRG,” he says.

Mission Accomplished

“It’s been a long time coming to destroy this stockpile,” says Jeffrey Brubaker, a technical adviser with PEO ACWA. “Over 30 years, first coming up with the approval to test technologies and coming up with the necessary funding. These facilities are complex—years of construction and years of testing out the process before we go into operations.”

In emphasizing the magnitude of the accomplishment, Jackson noted the Pueblo plant was “on a trajectory of potentially finishing operations in the late 2020s, years past the mandated treaty deadline.”

She credited the team’s work developing the ICAM in helping the plant destroy the most vexing of the weapons. “That spirit of collaboration from all members of the team made all the difference,” she says.

Now with the initial operations complete, the government turns to the closure process with all involved pleased with the results.

“This amazing accomplishment of safely completing destruction…has been no small feat,” says Kingston Reif, deputy assistant secretary of defense for threat reduction and arms control, in announcing the completion of work at Pueblo.

“The safety of the workforce, public and environment has always been priority number one for this program and the department,” adds Deborah Rosenblum, assistant secretary of defense for nuclear, chemical, and biological defense programs. “This achievement demonstrates our credibility in the eyes of the international communities and has helped move the U.S. government one step closer to closing this particular chapter of U.S. military history.”

CRG is now bringing its expertise from these projects to the military’s efforts to modernize munitions production. CRG is assisting American munitions manufacturers with its collaborative and innovative approaches to simplify and speed up their complex processes as they increase output to support Ukrainian forces.

The company has received multiple honors for its military focus, including being named among TIME’s Best Inventions of 2023 and ranking No. 14 on the Vet100 list of fastest-growing veteran-owned businesses. I have also been selected to participate in the prestigious CEOcircle program for entrepreneurial military veterans organized by JPMorgan Chase and Bunker Labs.

ASSEMBLY ONLINE

For more information on staking, read these articles:

Robots Automate Disassembly of Chemical Weapons

Springs, Stampings and Firearms

One Lean, Mean Airplane

.jpg?height=300&t=1725544628&width=300)